This spring, nearly half of all students in the Maynard (MA) Public Schools students told a student researcher just how often and in what ways they encountered media literacy instructional practices in their school district. This survey was administered by a high school student who worked with her school teacher-librarian Jean LaBelle, who also serves as the senior project coordinator at Maynard High School in Massachusetts, along with Erin McNeil, executive director of Media Literacy Now.

As a part of her senior project, Gracie Gilligan adapted the survey developed by Renee Hobbs and colleagues at the University of Rhode Island to find out whether more than 500 elementary and secondary school students (in Grades 4 thrare getting opportunities to access, analyze, and create media, using reflection and social action to examine news, information, advertising, social media, and more. While the Rhode Island survey had asked teachers, librarians, school leaders, community members and parents to estimate students’ exposure to media literacy lessons, Gracie Gilligan decided to ask children and teens directly.

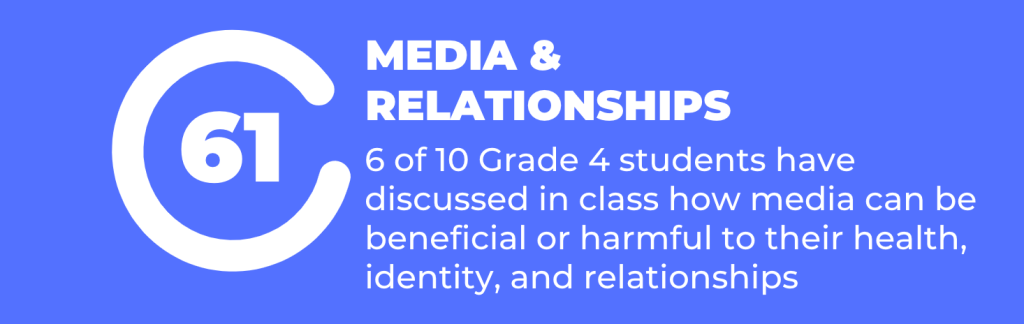

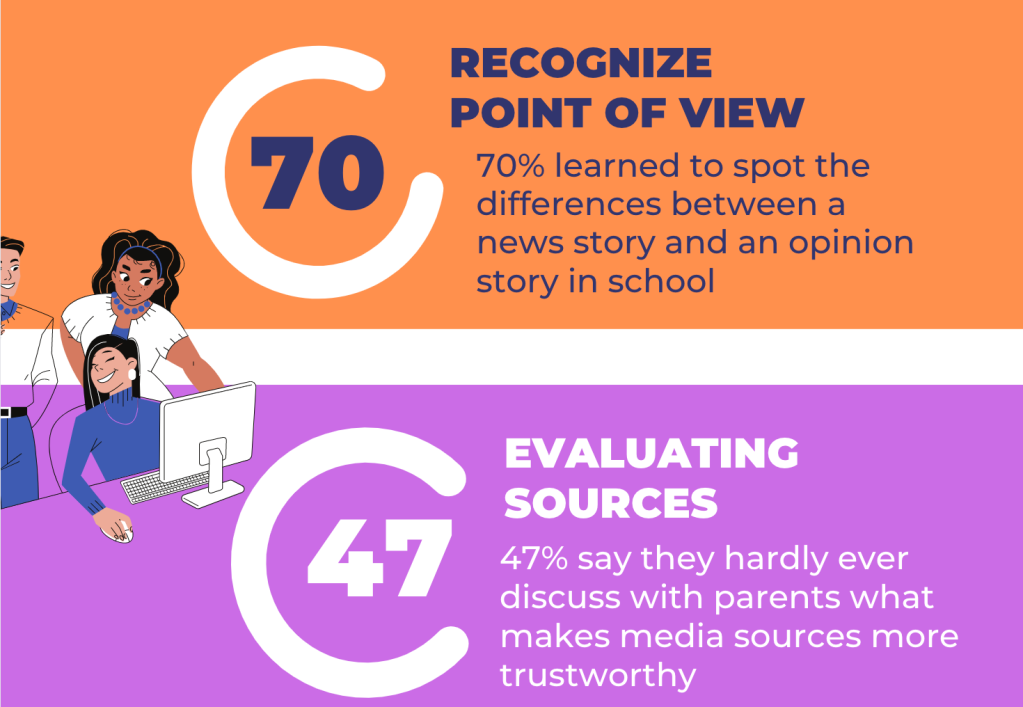

The good news: Students in Maynard report that many media literacy instructional practices are being implemented in the Maynard Public Schools. For example, two out of three students have discussed in class how media can be beneficial or harmful to their health, identity, and relationships, including 61% of 4th graders. Nearly 80% of 12th graders say that they have had lessons that help them differentiate between a news story an an opinion story in the news. 66% of students say they have learned about how the First Amendment and other laws give you freedom of speech and help you learn how to use that freedom responsibly.

However, there are still areas where Maynard can improve. Only 34% of students in Grades 4 – 12 have looked at media to identify stereotypes, and only half of 12th graders say that they have learned how selling audience attention is the way media companies make money. Fewer than half of students have had the opportunity to create a social action or awareness campaign to promote an event or motivate people to take action. Maynard history teacher Olga Doktorov says that these results give food for thought as she is planning her instruction and curriculum for next year. She said, “I often ask myself what I want my students to know and remember 10, 20, 50 years after graduating from high school, and media literacy is certainly one of the things that come to mind. It is a skill that will be relevant in any profession my students choose and in their personal lives as well.”

Another key takeaway from this survey was that parents and guardians of Maynard students are largely not helping them to develop media literacy competencies. Only 7% of students have often worked with parents or guardians to create videos or other media together. Only 12% often comment on the pros and cons of online life with their parents or guardians. Half of all students reported that they hardly ever discuss what makes media sources trustworthy with their parents/guardians. Most students report that they hardly ever read and discuss books, newspapers, or magazines at home and only 50% say that they discuss the pros and cons of life online. When parents are not actively involved in discussions about media and society with their children at home, schools must be responsible for ensuring that students are able to develop these essential life skills.

Maynard is a small community in Massachusetts with about 1,179 students enrolled in three schools. According to Census data, about 14% of the population are Hispanic students and about 20% of families are economically disadvantaged. When asked his opinion on the findings of this survey, Maynard High School Principal Charles Caragianes quoted President Franklin Roosevelt, who said, “Freedom of the press is essential to the preservation of a democracy; but there is a difference between freedom and license. Editorialists who tell downright lies in order to advance their own agendas do more to discredit the press than all the censors in the world.” Principal Caragianes says that this “really gets at the heart of media literacy and its importance. It’s critical for a functional democracy to have citizens who can discern between valid information, opinions, and outright lies. Media literacy is one way to ensure that life in Maynard, in Massachusetts, and in the United States flourish in ways that enable students to reach their true potential as citizens in a media- and technology-saturated society.

Comments(0)